|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 19

Yukon Transportation: A History

by Gordon Bennett

The Military Legacy

I

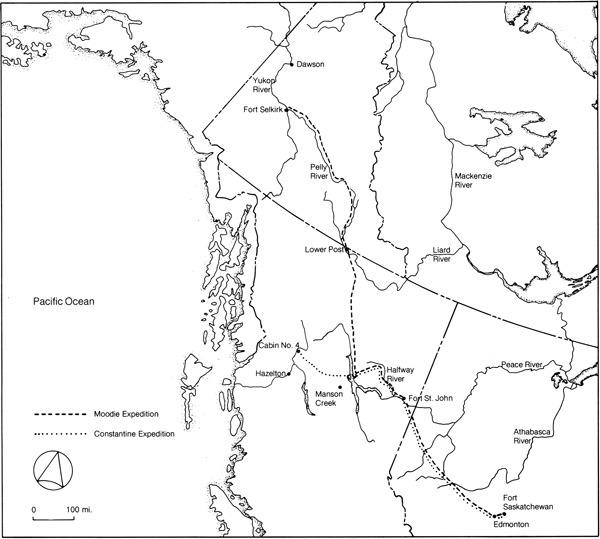

Unlike the First World War, the impact of which was virtually negative,

the post-Pearl Harbor phase of World War II engendered a massive

investment in northern transport facilities that was directly related

to the war effort. Of these most important, insofar as it related to the

territorial transportation system, was the construction of the Alcan

Military Highway.

II

Stripped of its strategic character, the Alcan Military Highway can be

seen as the last and only successful essay in a series of attempts that

spanned half a century to provide the Yukon with an overland link with

the outside. As early as 1897 Commissioner Herchmer of the North-West

Mounted Police, in anticipation of a deluge of Canadian gold seekers

over the so-called "Back Door Route" to the Klondike, had commissioned

Inspector J.D. Moodie "to collect exhaustive information on the best

road to take parties going into the Yukon via [the Edmonton-Pelly]

route." Moodie was instructed to identify those sections "where a wagon

trail can be made without expense," to report on water crossings that

would require bridges or ferries, to take note of the availability of

fuel, feed and hay, and to select sites that were suitable for the

construction of supply depots. With four fellow officers, an Indian

guide and a Métis, Moodie left Edmonton on 4 September 1897. His supply

kit was meagre, consisting solely of 100 pounds of pemmican. The

expedition was ordered to live off the land and to keep the pemmican

"until the last resource." Moodie was scheduled to reach the Yukon

that winter, at which time, Herchmer told him, the pemmican might be the

only "means of taking your party into the Klondyke."1

Both rations and schedule were soon to prove terribly unrealistic. The

expedition did not reach Fort St. John until 1 November and another

month elapsed before preparations for the next leg of the trip were in

order. Beyond Fort St. John, Moodie encountered a series of unexpected

obstacles. Winter travel made living off the land extremely difficult. A

succession of unreliable guides and terrain that was arduous and

largely unexplored slowed the party considerably. The trading posts upon

which Moodie was dependent for provisions were habitually undersupplied

with the result that the expedition was unable to replenish its stores.

Caches, which advance parties had established at designated points along

the route, were gone when the main party reached them, stolen by local

natives or stampeders en route to the Klondike.2

123 Routes of the Moodie and Constantine expeditions.

(Map by S. Epps.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

Eleven months after setting out from Fort St. John, Moodie's spent

and haggard party reached Fort Selkirk. The great stampede was almost

over, leaving in its wake little need for an Edmonton-Pelly road to the

Yukon. In his final report to Herchmer, Moodie wrote that "with regard

to the usefulness of this route to the Yukon, I should say it would

never be used in the face of the quick one via Skagway and the White

Pass."3 It would take 50 years and the Alaska Highway itself

to vindicate Moodie's opinion.

Undeterred by Moodie's conclusions and a declining Yukon economy, a

second, more ambitious scheme was broached; to blaze a road between

Edmonton and the territory. Once more the task of construction fell to

the Mounted Police, and on 17 March 1905 Superintendent Charles

Constantine, whose association with the Yukon dated back to 1894 and the

halycon days of Forty Mile, set out from Fort Saskatchewan with a party

of 31 for the southeastern terminus of the proposed road, Fort St. John.

Constantine's instructions were to build a 750-mile-long, 8-foot-wide

wagon road, to corduroy those sections located in bog and marsh, to

install necessary bridging and to construct roadhouses at 30-mile

intervals. With only the most primitive of tools at its disposal, the

party completed 94 miles of road during its first season and added 134

more, bringing the road to a point 20 miles west of Fort Graham, by the

fall of 1906. In September 1907 the detachment reached cabin number 4 on

the British Columbia-Yukon telegraph line, 377 miles from the base camp

at Fort St. John. Work was not resumed in 1908 because negotiations with

the government of British Columbia over financing that province's

portion of the road broke down and as a consequence, the road, fittingly

described by later writers as the "Road to Nowhere," was

abandoned.4

Twenty years were to elapse before another scheme to link the

northwest corner of the continent by road was to capture popular

attention. This time the initiative shifted from Canada to Alaska where

a territorial engineer from Fairbanks, Donald MacDonald, mounted a

vigorous campaign to unite Alaska with the mainland. Unlike previous

Canadian efforts to link the Yukon with the outside, which had generated

little if any public interest, MacDonald was able to enlist the support

of the International Highway Association and with the slogan "Seven

million dollars purchased Alaska for the United States, seven million

more will make Alaska one of the United States," win wide public

acceptance for the project in Alaska and Washington state and the

endorsement of a number of national associations in the United States.

Although the Yukon did not figure directly in the scheme, certain

residents in Dawson organized a chapter of the International Highway

Association as a demonstration of their own particular interest in the

road. As well, the province of British Columbia, through which the major

portion of the proposed road was to be located, showed a keen interest

in the scheme.5

The project gained momentum when in April 1929 the Alaska legislature

proposed that representatives from the United States and Canada be

convened to study the question. The American initiative continued into

1930 when Congress authorized the president to appoint three "special

commissioners to co-operate with representatives of the Dominion of

Canada in a study regarding the construction of a highway to connect the

northwestern part of the United States with British Columbia, Yukon

Territory and Alaska." A Canadian commission was appointed the following

year which included George Black, MP for the Yukon. In October the

American commission met with its Canadian counterpart in Victoria where

exploratory discussions on the technical and economic aspects of the

proposed highway took place. Two years later the United States

commission submitted its report to Congress. It concluded that the

"highway is a feasible project and can be built at reasonable cost" and

recommended that negotiations be undertaken to ascertain Canada's

interest in proceeding with the scheme.6

A lack of interest on the part of the Canadian government is

suggested by its failure to publish a separate report of the Canadian

commission's findings. For George Black the entire experience must have

been exasperating. His constituents spoke with practically one voice in

support of the highway, advocating its construction as a make-work

project. Except for the indomitable T. Dufferin Pattullo, who as premier

of British Columbia had a vested interest in seeing the discussions bear

fruit, Canadian support for the scheme was very limited.7

The general election of 1935 did not result in any immediate

modification of the Canadian position. Mackenzie King's economic

programme was, if anything, less ambitious than his predecessor's and

the relief aspects emphasized by the highway's proponents failed to

impress him. American pressure was not so easily thwarted, however, and

in March 1936 the United States raised the issue again. King did not

reply directly to the United States government, but submitted the

highway proposal to the Department of National Defence. The department

argued that the highway "would provide a strong military inducement to

the United States to ignore our neutral rights in the event of war

between that country and Japan" and strongly advised against Canada

participating in a joint highway venture.8

Armed with the opinion of his military advisers, King travelled to

Washington in March 1937 to discuss, among other things, the proposed

highway. Ironically, both in prospect and retrospect, Roosevelt

emphasized the highway's potential military value "in the event of

trouble with Japan." King conceded, somewhat misleadingly in view of

advice tendered by the Department of National Defence, that "that was a

matter which could be looked into," but refused to commit himself "as to

the possibility of any construction."

For the moment Canadian neutrality had been successfully defended,

but Roosevelt's persistence found an ally in Premier Pattullo who proved

far more responsive to the needs of West-Coast defence and the Alaska

highway than Ottawa. Pattullo's public pronouncements urging the

American government to exert strong pressure on Ottawa greatly chagrined

the prime minister who was extremely sensitive on the issue of Canadian

autonomy. According to James Eayrs, Pattulo's actions had the effect of

confirming the cabinet's determination "that nothing should be done." As

for suggestions that the United States take full responsibility for

funding the project, King replied that "grounds of public policy would

not permit using the funds of a foreign Government to construct public

works in Canada. It would be, as Lapointe phrased it, a matter of

financial invasion, or as I termed it, financial

penetration."9

In 1938 the United States chief of staff reported that "the military

value of the proposed highway is so slight as to be

negligible."10 Coincidentally, a Canadian interdepartmental

committee submitted a report to the government which outlined a number

of advantages to be gained from building the highway. These included

opening up new territory for settlement; resource, tourist and

recreational development; facilitation of air traffic, and unemployment

relief. In the meantime, President Roosevelt, at the behest of Congress,

had appointed a five-member commission to

cooperate and communicate directly with any any any similar agency

which may be appointed in the Dominion of Canada in a study for the

survey, location, and construction of a highway to connect the Pacific

Northwest part of continental United States with British Columbia and

the Yukon Territories [sic] in the Dominion of Canada and the

Territory of Alaska.

In a seeming reversal of its previous position, the Canadian

government passed an order in council on 22 December 1938 appointing a

five-member commission

to enquire into the engineering, economic, financial, and other

aspects of the proposal to construct the said highway to Alaska and to

meet for the purpose of discussion and exchange of information with the

United States Commission.

That the reversal was more apparent than real is suggested by the

preamble to the order in council which mentioned the repeated

representations from British Columbia and the United States and was

worded to suggest that the decision to appoint a Canadian commission was

a concession to these pressures. Nevertheless, it can be inferred that

the most obnoxious features of the highway proposal, that is, those

aspects which might compromise Canadian neutrality and autonomy, had

been removed. In the time-worn tradition of Canadian politics, a

tradition that was raised to the level of a high art by Mackenzie King,

the government appointed a commission, the sole purpose of which was to

study the problem.

The Canadian commission held a preliminary meeting at Victoria in

April 1939. This was followed by a series of public meetings, one of

which was held in Whitehorse. A number of local representatives were

heard, all but one registering support for the proposed highway. The

sole dissenting voice was that of W.D. MacBride who read a prepared

statement on behalf of Herbert Wheeler, the president of the White Pass

and Yukon Route. MacBride argued that the cost of the proposed highway

far exceeded any benefit that would accrue from its construction. He

declared that the road would be superfluous, that the "Yukon is amply

supplied with transportation facilities now." He suggested that the

airplane was and would continue to be a far more effective tool in

developing the territory than any highway.

While MacBride expressly disavowed any conflict of interest, it is

obvious that the White Pass and Yukon Route considered the proposed road

to be a serious threat to its own operation. Although the company was

undoubtedly sincere in questioning the validity of the scheme —

there was barely enough traffic to keep its own operation going —

the company's opposition must be viewed in the light of the potential

impact of another access route on its balance sheets. The real issue, as

identified by the inhabitants of the territory, was cheap transportation

and a suspicion prevailed, the apparent economic difficulties of the

White Pass and Yukon Route notwithstanding, that the company was taking

advantage of its monopoly and that an alternative form of transportation

would be cheaper than the service provided by the White Pass and Yukon

Route.

The commission's almost cursory forays into Whitehorse and Carcross

marked the first and last time that an opportunity was provided for the

territory to participate in the discussions. Thereafter, the commission

concerned itself with the accumulation of specific data relating to

possible routes, construction costs and financing. Paradoxically, in

view of the highway's ultimate location, the request for a hearing from

interests representing Edmonton was rejected on the grounds that the

order in council creating the commission had specifically confined its

consideration to routes through British Columbia. Throughout the 1930s,

routes through British Columbia were the only ones to receive serious

consideration in Canada and United States. The Edmonton route, which the

Canadian government had actively promoted at the turn of the century,

fell into disfavour, largely because the initiative for the highway

during this period came from the United States.

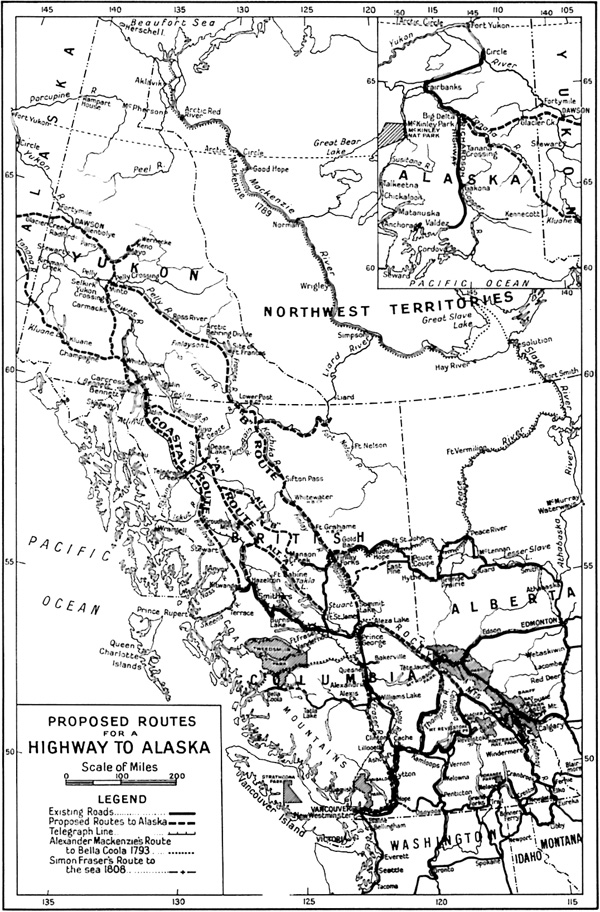

An aerial reconnaissance programme was undertaken in 1939 to

investigate the three British Columbia routes then under

discussion.11 Each of them originated at Prince George

although in the case of the "coastal" and "A" routes, Hazelton, 300

miles northwest of Prince George, was selected as the projected point

for new construction to take advantage of the existing highway between

them. The western or "coastal" route, as it was designated, ran through

Hazelton and followed the Skeena River west to Kitwanga. From Kitwanga

the route struck north, skirting the Nass, Bell-Irving and upper Iskut

rivers to Telegraph Creek. From Telegraph Creek the route followed the

telegraph line through Atlin, Tagish, Carcross and Whitehorse. At

Whitehorse the route followed a westerly course to Kluane Lake via

Champagne and Kluane, thence northwest to the headwaters of the Tanana

River, linking up with the Richardson Highway at Big Delta in

Alaska.

The "A" route, located east of the coastal route, followed the

telegraph line out of Hazelton to the Klappan River. From the Klappan it

ran north to the Stikine, followed the east bank of the Taya River to

Gun Lake, crossed the Nakina and linked up with the telegraph line to

Atlin. An alternate "A" route, running out of Fort St. James at Takla

Lake, converged on the main route west of the upper Skeena River.

The "B" or Rocky Mountain trench route originated at Prince George,

followed the Parsnip River to its confluence with the Finlay at Finlay

Forks, and continued along the Finlay to Sifton Pass. From Sifton Pass

it ran along the west bank of the Kachika, over the divide to the Liard

and Frances rivers, and down the Pelly to Pelly Crossing. From Pelly

Crossing it followed the Overland Trail to Dawson, linking up with the

Richardson Highway from Glacier Creek.

The coastal route was found to be impractical on the basis of aerial

reconnaissance. Although it furnished land access to towns along the

coast and surpassed the other routes in terms of scenery — an

important factor in assessing tourist potential — it failed to

satisfy the conditions established for engineering feasibility and cost.

River valleys were deep and passes through the mountains were

correspondingly high while heavy precipitation made year-round operation

questionable and portended excessive expenditures for

maintenance.12

The commission recommended that field work be continued on route "A"

during 1940 in order to complement the information already obtained on

route "B."13 The commission submitted its final report in

1941. While the commission found that cost, engineering feasibility and

tourist potential were not decisive factors, mineral potential,

proximity to the Peace River agricultural belt and air routes favoured

the "B" or Rocky Mountain Trench route.14

The coastal route, which had long been favoured by the United States,

especially that portion following the air route into Alaska from

Whitehorse, was completely bypassed by the Canadian commission's

recommendations. Whitehorse, the transportation hub of the Yukon, lay

some 200 miles due west of the proposed road; 13 years of American

initiative had been crowned by a Canadian report which almost totally

ignored the wishes of the United States. Whether the American government

would have maintained its interest in the highway, given the Canadian

preference for a road through the Rocky Mountain Trench, must remain a

matter of conjecture for ultimately the fate of the highway proposal was

not to be settled by the United States or Canada, but by Japan.

III

On 7 December 1941 Europe's second war of the century exploded into a

global conflict. In what one American historian has described as an

almost perfect application of the laws of war, Japan's attack on Pearl

Harbor exposed the entire west coast of North America to enemy

attack.15 The proposed highway to Alaska, which had

languished through interminable bilateral discussions throughout the

1930s, assumed great urgency as Alaska's strategic importance, both for

North American defence and materiel support for Russia, became manifest.

The Alaska highway, which had failed of accomplishment in time of peace,

became a reality in time of war. "Fear," Edward McCourt has written, "is

a mighty stimulus to achievement."16

On 2 February 1942 the United States War Department ordered the

immediate preparation of a survey and construction plan for a military

road to Alaska. The Canadian government was informed of the plan on 13

February and approved it the same day, and on 14 February the United

States government issued a directive to proceed with the

project.17 A formal agreement was signed on 17 March 1942

outlining the respective obligations of the United States and Canada for

implementing the plan. Under its terms the United States undertook to

construct a military highway from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to

Fairbanks, Alaska, via Big Delta on the Richardson Highway. The American

government agreed to maintain the highway for the duration of the war

and for a period of six months following the cessation of hostilities,

after which that portion of the highway situated in Canada was to

become the property of Canada. For its part, the Canadian government

agreed to furnish necessary rights of way and local construction

materials, and to waive import duties, licence fees and income tax on

American companies and citizens.18

124 Proposed routes for a highway to Alaska.

(Canadian Geographic Journal.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

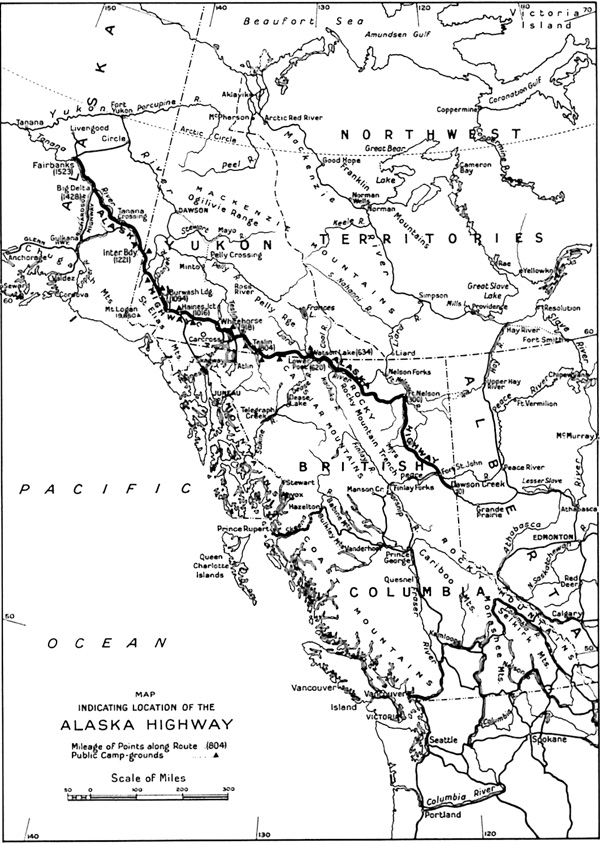

125 Alaska Highway.

(Canadian Geographic Journal.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

The existence of a series of airfields between Edmonton and Whitehorse

proved to be a decisive factor in determining the location of the

proposed highway. Known as the Northwest Staging Route, this series of

airfields satisfied the strategic requirement for an inland route to

secure the highway from enemy attack and had the added advantage of

being tributary to Edmonton so that supplies for the highway could be

moved over existing land and air routes should the West Coast ever be

closed to shipping. It should not be assumed that the staging route was

assigned an entirely auxiliary role, however, for the highway was

intended not only to meet the "need for a year round truck route for the

movement of freight to Alaska," but also to provide ground access to

the staging route airports in order to facilitate the transport of

supplies to Russia.19

Conceived in 1939 as a means of facilitating civilian air travel between

Edmonton and Whitehorse, the Northwest Staging Route was the name given

to a series of airports built at Grande Prairie, Alberta, Forts St. John

and Nelson in British Columbia, and Watson Lake and Whitehorse in the

Yukon. A complementary feature of the Northwest Staging Route was the

construction of a number of emergency landing fields "in accordance with

standard airway practice" at intermediate points along the way.

Construction began in 1940 and by September 1941 the route was opened

to aircraft flying by visual flight rules. All-weather flying was begun

in December following the installation of radio ranges.20

While construction of the Northwest Staging Route occurred

coincidentally with the first two years of the war, it was not until the

United States became a belligerent that the air route's original

commercial character was altered. The American declaration of war and

the decision to proceed with the highway forced a reconsideration of

the non-military use for which the route had been designed. Beginning in

1942 the principal airfields were enlarged, navigation facilities were

augmented and hangars, workshops, refueling systems and airport lighting

were added. Living accommodation was expanded and power and water

services were increased. All this was done over a period of 18 months

and completed in July 1943.21

Locating the highway was no easy matter since virtually no one had any

firsthand knowledge of the terrain to be traversed.22 For

this reason much of the actual locating of the right of way was left to

the discretion of surveyors in the field.23 Where the

topography of a specific region suggested that a certain airfield could

best be reached by a branch road instead of the main highway, such a

deviation was permited. As one observer has aptly noted, the highway

"follows the line of least resistance." This was the result of a

construction plan that demanded "an alignment that would ensure

completion of the road as a practical military highway in the minimum

possible time employing the maximum forces and

equipment."24

Under a phased construction plan conceived by the War Department, the

Alcan Military Highway was to be built in two stages. The first stage

called for the construction of a pioneer or tote road to be built by the

United States Army Corps of Engineers, the second for a finished gravel

highway to be built by civilian contractors working under the authority

of the United States Public Roads Administration. Original

specifications called for a permanent highway with a 36-foot grade, the

middle 20 feet to be surfaced with crushed rock or gravel. This was

subsequently modified to a grade of 26 feet west of Fort St.

John.25

Construction began in March 1942. In all about eleven thousand military

personnel divided into seven regiments were assigned to the project. To

expedite construction, the proposed road was divided into six sectors;

Dawson Creek to Fort Nelson, Fort Nelson to Lower Post, Lower Post to

Teslin, Teslin to Whitehorse, Whitehorse to the international boundary

and the international boundary to Fairbanks. This enabled work to

proceed simultaneously on each sector. Within each sector six

construction crews were deployed, each crew building approximately 20

miles of road, then leapfrogging to the head of

construction.26

Despite the variety of topographical features traversed by the highway,

a basic construction technique was developed that combined the virtues

of flexibility and common application. Each stage in the construction

process was designed so that it proceeded in descending priority in

order "to keep the lead tractors moving ahead as fast as possible." The

right of way was first marked by locating parties. Advance tractors then

moved in and cleared a swatch 50 to 100 feet wide. They were followed by

bulldozers that levelled the right of way and did rough grading. The

bulldozers were followed in turn by ditching and culvert crews and

finally by finished grading crews.27

126 A U.S. Army engineer reconnaissance party surveys the

ground for a suitable right of way for the Alaska Highway.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

127 A bulldozer clears the right of way.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

In its effort to maintain a rate of construction consistent with the

urgency attached to the project, the army was constantly thwarted by

river and creek crossings located on the right of way.

While many such breaks in the highway system could be forded, at least

for construction purposes, all required some form of bridging sooner or

later since the road functioned as its own supply line.

The slow pace of bridge building — bridge crews generally trailed

far behind the other construction teams — was partially offset by

the use of pontoons. Lashed together, floored with planking and

equipped with outboard motors, the pontoons could be converted into

serviceable ferries that permitted the transfer of men and equipment

from one side of a river or creek to the other. With the construction of

a landing slip, a portable bridge could be fashioned by connecting a

series of pontoons, covering the surface with timber and anchoring each

end to a deadman. The ferries could then be dismantled and sent ahead

to the next crossing.28

All traffic was moved over these pontoon bridges until bridge-building

teams replaced them with more permanent structures. Instead of adopting

the conventional but time-consuming practice of sinking piles for

supports, cribs were used. While not as permanent as the pile-type

support, cribs, which were open-topped log boxes filled with rocks,

could be quickly constructed. With a steel sheet cut from empty fuel

drums to protect them from ice damage, the cribs were permanent enough

to satisfy the highway's immediate military objective.29

Muskeg and permafrost also caused a number of delays, first because they

required special treatment and second because the army dealt with

permafrost during the initial stages of construction as though it were

the same phenomenon as muskeg.30 Whereas muskeg removal was a

necessary preliminary to the creation of a stable road surface,

stripping the surface material or muck that covered permafrost had the

opposite effect since it exposed a once stable subsurface to the melting

action of adjacent surface temperatures and the sun. It was only after

a period of trial and error and by discussing the problem with

experienced local road contractors that the army adopted a method that

was similar to that employed by territorial road builders during the

first decade of the century. This procedure involved a minimum

disturbance of permanently frozen ground, the recovering of stripped

sections to inhibit melting and the adding of brush to increase

insulation.31

The two-phase construction schedule established in Washington

quickly broke down under the massive and constant flow of men and

construction equipment over the completed portions of the pioneer road

with the result that the road rapidly deteriorated.32 In

retrospect it seems apparent that the planners failed to appreciate the

intensive use to which the road would be put during the early stages of

construction. As a consequence, the two-phase construction programme was

abandoned in early August 1942 and the Public Roads Administration,

which had been in Whitehorse since mid-May letting contracts to civilian

road builders for the final phase of the work, was called

in.33

Of the many problems associated with the building of the Alcan Military

Highway, none was greater nor more persistent than supply.34

Like the gold rush of 1897-98, the Alcan project placed an enormous

strain on the northern transportation system. Had conditions existed for

a substantial degree of local participation in the project, much of the

pressure that was brought to bear on the region's four supply routes

— the Northern Alberta Railway, the White Pass and Yukon Route

railway, a road from the port of Valdez, Alaska, and the Alaska

Railroad — would have been relieved.35 But local

participation was necessarily slight and the army and private

contractors were almost entirely dependent on outside sources for

manpower, material and equipment. When it is remembered that the prewar

impetus for the highway had sprung from a widely held notion that those

transportation facilities supplying the region were inadequate, it is

hardly surprising that these same facilities, none of which had been

designed for sustained, intensive use, proved to be deficient under

conditions of massive demand created by Alcan.

Geography and the logistics of transportation threw the principal

burden of supply onto the White Pass and Yukon Route railway. The

railway, with its terminus at Whitehorse, midway between Dawson Creek

and Fairbanks, gave access to the highway at four points instead of two

and greatly facilitated construction.36 As a consequence, the

White Pass and Yukon Route railway became the project's main supply

line and Whitehorse its principal distributing point.

Whitehorse's de facto emergence as the operational centre of the Alcan

project — an emergence that was directly attributable to the White

Pass and Yukon Route railway — was given formal recognition by the

establishment of the Northwest Service Command at Whitehorse on 4

September 1942. Created by general order of the United States War

Department, the Northwest Service Command became the co-ordinating

authority for all activities of the United States Army in Alberta,

British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, the Yukon and

Alaska.37

128 A construction crew lays corduroy over muskeg.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

129 A river crossing effected by laying planks over the ice

on the Peace River.

(Public Archives of Canada.)

|

130 Sternwheelers transported supplies needed to build the

Alaska Highway and the Fairbanks pipeline. This barge at

Dawson is loaded with U.S. Army trucks.

(Yukon Archives.)

|

One of the first tasks undertaken by the Northwest Service Command

was to increase the supply capacity of the railway. Although the White

Pass and Yukon Route had made every effort to satisfy military

requirements, first by running one train a day, then by hauling five

hundred tons daily, the task had proved too large. When in August 1942

the army asked the company to handle two thousand tons a day, C.J.

Rodgers, the president of the White Pass and Yukon Route, realized that

wartime restrictions on labour and rolling stock made compliance

impossible and suggested that the army assume the operation of the

railway.38 This timely suggestion was accepted by the

Northwest Service Command and on 1 October 1942 the railway was leased

for $27,708.33 a month. The railway was subsequently assigned to the

770th Railway Operating Battalion and a large railhead was built at

MacCrea, eight miles outside of Whitehorse.39

The highway was not the only defence project in the Canadian North to

benefit from the increased supply capacity of the railroad. Cement for

airport runways and steel girders for hangers were shipped over the

railway for the Northwest Staging Route as were pipeline sections and

cracking retorts for the Canol project; a massive scheme designed to tap

the oil at Norman Wells in the Northwest Territories, pipe it to

Whitehorse and refine it there.40 The most ambitious, if not

the most expensive, of the three major defence projects undertaken in

the Canadian Northwest during World War II, the Canol project was

designed to supply the oil requirements of the armed forces in the

Canadian North and Alaska. Begun in June 1942 under the terms of an

agreement similar to the one dealing with the Alcan Military Highway and

completed two years later, the project involved the laying of a

four-inch crude oil pipeline between Norman Wells and Whitehorse, the

construction of two ancillary pipelines from Whitehorse to Skagway and

Fairbanks, the erection of an oil refinery at Whitehorse and the

construction of a road running parallel to the pipeline from Norman

Wells to mile 836 on the Alcan Military Highway.41

On 20 November 1942 the eastern and western sections of the Alcan

Military Highway were joined at Soldiers' Summit, 151 miles northwest

of Whitehorse. On 21 November the road was officially opened. Excepting

a 150-mile section between Kluane Lake and the Alaska boundary which was

only passable when the ground was frozen, the 1,523-mile pioneer road

was completed in just over eight months and opened to through military

traffic.42

Except for two troop companies that were not relieved until July 1943,

all military personnel directly involved in the construction of the

highway were withdrawn before the beginning of the 1943 construction

season. Completing the road to final specifications subsequently

proceeded under the direction of the Public Roads Administration which

employed some 81 private contractors and 14,000 civilians over the

following two years. At the request of the United States government, the

highway was renamed the Alaska Highway on 19 July 1943.43

The Public Roads Administration was left with a task that was almost as

large as the construction of the pioneer road itself. Built in haste,

much of the pioneer road was substandard. Drainage was generally

inadequate, many sections of the road having been poorly located or

built only slightly above ground-water level. Natural insulation

protecting permafrost had been disturbed. Excessive curvatures and

gradients were not uncommon. The southern end of the highway was located

through a noncohesive, unstable soil region known as the Bear Paw silts.

As a consequence, a substantial amount of relocation and reconstruction

was necessary. All the corduroy put down during 1942 was torn out and

replaced, and the highway was resurfaced in its entirety. The log

bridges constructed by the army were supplanted by steel structures. The

Kluane Lake-Alaska boundary section was rebuilt; freight for Fairbanks

being shipped downriver from Whitehorse to Circle, Alaska, for

transhipment over the Steese highway to Fairbanks in 1943.44 In

addition, a road was built from the all-weather port of Haines, Alaska,

to Johnsons Crossing, mile 1,016 on the main highway.

Maintaining the remote fifteen-hundred-mile highway was a major task.

Supplies and accommodation had to be provided for maintenance crews on

the more isolated sections of the road and spare parts for machinery and

equipment had to be stocked for any contingency. Summer maintenance was

relatively simple, consisting for the most part of grading and

sprinkling the gravel surface.45 Winter maintenance, on the

other hand, was more complex, especially on sections of the highway that

were poorly located and susceptible to winter icing. Permafrost springs

and glacial streams adjacent to the highway were particularly

troublesome in this regard; the former because they "bled" during the

coldest weather, forming massive ice deposits on the highway surface,

the latter because they froze in such a way as to sometimes alter course

and damage the highway, bridges and bridge approaches.46

Light precipitation cut snow removal to a minimum and the snow furnished

an excellent road surface, superior in fact to gravel itself, but

combined with extreme cold, the light precipitation permitted a high

degree of frost penetration and contributed to the high cost of spring

maintenance.47

IV

The building of the Alaska Highway was an anomaly in the history of

transportation development in the Yukon. Although more than one-third of

the highway was located within its boundaries, the Yukon played no part

in the decision to build the highway and only a negligible role in its

construction. To be sure, a highway to the outside had long been hoped

for, but the Alaska Highway can not in any way be described as the

fulfillment of that aspiration. The Alaska Highway was built to satisfy

a limited military objective; it was not a product of local economic

conditions nor was it built to provide the Yukon with an alternative

outside access route. The Yukon was incidental to its construction and

as a consequence little consideration was given to what immediate,

short-term impact the highway was to have on the territory. Nowhere was

this more clearly demonstrated than in the wartime operation of the

White Pass and Yukon Route railway.

For almost two generations the railway had been the Yukon's umbilical

cord; a life-sustaining artery that was as vital to the territory as

mineral production itself. For this reason the decision to build the

highway, while greeted with patriotic fervour by most of the local

residents, was accompanied by an apprehension that the movement of

territorial supplies over the railway might be adversely affected by

military requirements. Unfortunately, this early apprehension was not

misplaced. On 3 June 1942 George Black, MP for the Yukon, rose in the

House of Commons to protest American objections "to anything being

brought up by steamers on the west coast or by rail, mining machinery

and even food for the inhabitants of that part of the country." In an

attempt to resolve the problem, G.A. Jeckell, the territorial

controller, was appointed local agent to the wartime superintendent of

transportation, "with power to deal with that matter on the

spot."48

While Jeckell's appointment afforded some measure of satisfaction, the

situation deteriorated after the army leased the railway in October

1942. According to Jeckell, the takeover resulted in an immediate decay

of local service. "Very little freight was handled" during the winter of

1942-43, Jeckell wrote, "and large quantities of perishable

freight [were] not moved and allowed to freeze at Skagway." In

response to local criticism, C.K. LeCapelain, a Canadian liaison

officer, denied that "the civilian population of the Yukon was [being]

discriminated against." While admitting that there was inexperience,

incompetence and irresponsibility in the military's operation of the

railway, LeCapelain wrote that

the trouble really starts back in Edmonton, Prince Rupert, Vancouver

and Seattle where various U.S. agencies, mostly under the control of the

Divisional Engineers. . . start to pour thousands of tons more

freight into Skagway than the port or railway can

handle.49

The question of which should take precedence, military supply or

local supply, was never resolved to the complete satisfaction of the

inhabitants of the territory and perhaps it is not too trite to suggest

that it could not be. The supply question did not become a crisis,

however, because it was relatively short-lived. By late

1943 demand had levelled off and the army had become a great deal more

efficient in operating the railway.

If the building of the Alaska Highway were to be told from a Yukon

perspective instead of the conventional military perspective, a much

different picture would emerge. An influx of thousands of troops which

more than doubled the territory's population did not occur without

disruption. This theme and the corollary theme of friction between the

military and local residents have been all but obscured in the

literature on the highway. In its haste to complete the highway, the

United States Army took little heed of Yukon sensitivities and tended to

regard the feelings of many inhabitants as an obstacle to its main task.

Herbert Wheeler expressed the attitude of many Yukoners when he wrote

that the army "treated our people as if we were inferior beings and

generally made themselves obnoxious."50

V

Approximately 342 million dollars were spent on transportation and

related projects in the Canadian Northwest during World War II. Of this

total, a disproportionate share was spent in the Yukon, but this

expenditure, massive as it was, left little more than a dubious legacy.

The Canol complex, built at a cost of $133,111,000, was abandoned in

1945 although a portion of the road was later reopened. The Northwest

Staging Route, designed for prewar flying conditions, was rendered in

large part obsolete by the wartime advance in airplane and

communications technology.51 Even the Alaska Highway, the

most important of these three major projects, failed to generate the

benefits so long anticipated from an alternate access route to the

northwest part of the continent.

The highway's impact on traditional Yukon trading patterns could not be

tested during the war. Until June 1943 no commercial or civilian

traffic was allowed on the facility, after which all non-military

carriers were required to make application to the newly created Joint

Traffic Control Board for permission to use the road. The board screened

each application and issued permits only to those whom it deemed to

have "legitimate" business on the highway. All other types of traffic

were excluded so that military transport would not be disrupted and

because of the absence of travel facilities such as service stations,

restaurants and overnight accommodation. In November 1943 a scheduled

bus service was established between Dawson Creek and Whitehorse under

the supervision of the Joint Traffic Control Board. Until the White Pass

and Yukon Route organized a highway division in October 1945, no

commercial carriers operated on the Alaska Highway.52

On 1 April 1946 that portion of the Alaska Highway located on Canadian

soil was ceded to Canada by the United States government in accordance

with the joint agreement of 17 March 1942.53 Because of the highway's

remoteness and the demand for manpower and equipment in other economic

sectors during the immediate postwar period, the highway was not placed

under civilian control. Instead, responsibility for its administration,

improvement and maintenance was assigned to the Whitehorse based

Northwest Highway System of the Canadian army.54 With the

exception of pleasure travel which remained restricted until February

1948, the highway was then opened to all classes of

traffic.55

The opening of the Alaska Highway was viewed in Seattle and Vancouver as

a challenge to the traditional monopoly theretofore enjoyed by

West-Coast ports over Yukon trade and transportation.56 In

Edmonton, on the other hand, which for half a century had promoted

itself as a gateway to the Yukon, the opening of the highway was

greeted with great anticipation. This anticipation was short-lived.

Although the highway was instrumental in bringing to an end the

exclusive monopoly of Seattle, Vancouver and the White Pass and Yukon

Route railway, it never attracted enough traffic to threaten their

continued commercial supremacy.

Several factors operated against the Alaska Highway ever becoming a

major competitive force in Yukon transportation. Even as the highway was

being built, the United States Army prepared contingency plans for a

railroad through the Rocky Mountain Trench in recognition of the

highway's inappropriateness as a transportation facility. Because the

highway was conceived as a military supply route, no consideration was

given to its postwar commercial potential. The highway's peacetime

usefulness was also diminished because the Yukon's principal producing

regions, the Dawson and Mayo districts, were bypassed. This precluded

any significant degree of local traffic generation and underlined the

dilemma of transforming a military supply road into a useful commercial

highway. As a consultant firm concluded in 1968, "the Yukon obtained

[in the Alaska Highway] a road link earlier than would otherwise have

been the case but was left with . . . a tortuous road in the wrong

place."57

More particularly, the failure of the Alaska Highway to attract a

significant share of Yukon traffic and to mount an effective challenge

against the White Pass and Yukon Route railway was attributable to the

high cost of highway transport. At a minimum user-cost of ten cents per

ton-mile (1948), just barely enough to ensure an adequate return to

highway carriers, the Bureau of Transportation Economics reported that

the highway could not compete with the railway. This shifted the burden

of competition to commodity wholesale prices. Here again the highway was at a distinct

disadvantage. Although Edmonton wholesale prices were slightly lower

than Vancouver prices on class-rate freight shipped over the Canadian

Pacific Railway from points east of Sudbury, the small amount of traffic

moving on class rates — "probably not more than 15%" — was not

enough to offset the high cost of highway transport or Vancouver's

wholesale price advantage on other commodities.58

Like other frontier regions, the Yukon has traditionally been "next year

country." Excepting the Klondike gold rush, which literally transposed

"next year" into the present, the territory has always looked to the

future for better times as though there were some inexorable edict of

history that progress was related to the passage of time. So it was with

the Alaska Highway. Its competitive limitations and burdensome

maintenance and improvement costs were borne, partly because political

expediency precluded following the Canol precedent and abandoning the

highway, and partly because it was hoped that the highway would develop

into a successful commercial artery.59 But time has not

solved the problems of the Alaska Highway. Despite postwar economic

expansion and the construction of the Hart Highway by the province of

British Columbia, a feeder road which gives access to the Alaska Highway

from Prince George via Dawson Creek, the Alaska Highway's importance as

an alternative route to the Yukon has in fact diminished. A comparison

of 1947 and 1964 commodity flows into and out of the Yukon shows that

while total highway freight tonnage increased from 26,656 tons in 1947

to 38,932 tons in 1964, the highway's share of Yukon traffic declined

sharply over the same period, from 38.1 per cent in 1947 to 22 per cent

in 1964. At the same time, the White Pass and Yukon Route railway, the

highway's principal competitor, increased its share from 58.5 per cent

in 1947 to 76 per cent in 1964. According to the Stanford Research

Institute, which prepared a report on the Alaska Highway in 1964, these

figures reflect a long-term trend.60

Although the Alaska Highway has failed to meet the expectations that

were anticipated of an alternate access route to the Yukon, it has

played and continues to play an important role in the territorial

transportation system. This is especially true in the southeastern

section of the territory around Watson Lake where the highway provides a

vital link to the outside supply sources and markets. However, one area

of transportation where the highway has never made much of an impact

and shows little indication of doing so is in the export of minerals. It

is this failure which explains in large measure the significant

imbalance that exists between the highway and the railroad. The highway

has done much better in the movement of high-revenue commodities such as meat and

produce, electrical appliances, machine parts and furniture. Petroleum

constitutes another source of traffic, accounting for almost one-third

of the highway's Yukon freight although here again, little petroleum

moves west of Watson Lake.61

Except for local traffic use in the immediate vicinities of Whitehorse

and Watson Lake, the Alaska Highway has probably made its greatest

impact on tourism. Despite its gravel surface, an oppressive dust

problem and frequent stretches of monotonous terrain on the heavily

travelled eastern section, the highway provides a less costly form of

tourist travel than air transport or the West-Coast ferry system. As a

consequence, the highway is the main gateway for the thousands of

tourists who visit the territory annually. Since the tourist industry

is the second largest and one of the fastest growing revenue-producing

industries in the Yukon, it seems clear that both tourism and the

highway will play significant roles in the future.62

Full exploitation of the territory's tourist potential depends in large

part, however, on eliminating the highway dust problem which makes

travel not only unpleasant but potentially hazardous. A growing segment

of opinion in the Yukon, alarmed at the unfavourable impression created

by the highway, is agitating for an asphalt surface.63

Although a 20-mile section of the highway in the Whitehorse area has

been paved, there appears to be little likelihood that the road will be

paved in the forseeable future. The experience of the Alaska Road

Commission indicates that maintenance costs tend to rise for paved

roads instead of decreasing.64 At an estimated improvement

cost of $167,651,000, paving would far exceed any possible benefit and,

as the Stanford Research Institute suggested, it might well have an

adverse effect on the highway's freight-carrying function through the

imposition of load limits.65

For all of its shortcomings as a transportation facility, the Alaska

Highway has had a major influence in shaping the course of territorial

development since 1945. The rise of Whitehorse to intermediate

metropolitan status, the transfer of the territorial capital and an

extended economic frontier have stemmed largely from the existence of

the highway. In a more direct sense, the administration and maintenance

of the highway have constituted an important local industry, employing a

stable labour force and bringing a welcome payroll independent of

mining.66

VI

The stampede of 1897-98 and the construction of the Alaska Highway,

the two most significant events in the history of the territory, have

invited comparison as to which was the more important. In 1965 the

Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources expressed the

opinion that the Alaska Highway "has probably done more to advance the

development of the Yukon than any other single endeavour, including the

Gold Rush." To be sure, the Alaska Highway has been an important factor

in the postwar development of the territory. The publicity given the

highway in popular periodicals as well as business and professional

journals was instrumental in interesting many in the Yukon's resource

potential and the highway itself fostered prospecting and mineral

development in areas that were tributary to it. For example, the Cassiar

Asbestos mines in northern British Columbia, the production from which

is shipped to market through the Yukon, owe their discovery and

exploitation to the highway.67 In terms of transportation,

however, the White Pass and Yukon Route railway, a legacy of the

Klondike gold rush, has far outstripped in importance the Alaska Highway

and given the importance of transportation in territorial development,

it seems obvious that the gold rush has played a greater role in

advancing territorial development than the highway. The highway itself,

moreover, owes its existence in part to some long-range consequences of

the great stampede. The Northwest Staging Route, a decisive

consideration in the decision to build the highway, would never have

been conceived, let alone built, had it not been for the gold rush which

attracted hundreds of people who remained in the territory after

1900.

|

|

|

|