|

|

|

Canadian Historic Sites: Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History No. 3

The French in Gaspé, 1534 to 1760

by David Lee

Part I: The Background

English, French, Scots and Indians

It was from the voyage of Giovanni de Verrazano in

1524 that first came the name "Nova Gallia" or "New France." This was

claimed to cover a large part of the Atlantic Coast of the New World.

Ten years later Jacques Cartier landed in Gaspé Bay and raised a

cross bearing, in relief, three fleurs-de-lis and the words "Vive le Roy

de France." When a Micmac chief protested that "all this region belonged

to him," Cartier assured him that the cross was meant only "to serve as

a landmark and guidepost on coming into the harbour."1 Some

scholars feel, however, that this simple act formally claimed the land

for France. Henceforth the French considered Acadia, Gaspé and

the St. Lawrence to be French and handed out authorizations to settle

the land and trade in furs. In 1623, Brother Gabriel Sagard landed at

Gaspé Bay and took "possession of that land for the Kingdom of

Jesus Christ;" but he was claiming it not from the Micmacs but from

"Satan and his imps."2

Although we have no population estimates, the Micmacs

were probably not very numerous in Gaspé. Despite the rugged

topography they lived a seasonally nomadic life. In winter they moved

into the woods where they hunted beaver, otter, moose, deer, bear and

caribou. The rest of the year they lived on the seashore, especially at

the mouths of rivers where they hunted seal, birds, eels, fish and

shellfish. The area was sacred to the Micmac for a legend claims that it

was at the mouth of the Restigouche River that God created man. At the

same time God gave Gaspé to his new creation.3

After Cartier, however, no thought was given to

Indian claims and the Indians never did challenge the French intrusion.

While by these presumptuous French declarations the Indians may have

lost (by European legal standards) their landed heritage to the French,

in reality they never felt this loss during the French regime. The

French in Gaspé were basically interested in exploiting the

fishing resources of the coasts and never ventured inland. Nevertheless,

Indian life in Gaspé was affected in all the other lamentable

ways that Indians throughout the New World suffered through contact with

Europeans. It was the fur trade which had permanently attached the

Indians to Europeans in New France, but in Gaspé the fur trade

was only a sideline to fishing. As a result, the faunal staples of the

Indians were probably not depleted as badly or as noticeably as

elsewhere. There was, however, some trade in furs, and inevitably and

irrevocably even this occasional trade altered the Indians' way of life

and they became irresistibly dependent on European technology. The

difference was that the process of acculturation was much more gradual

in Gaspé than it was, for example, in Acadia or Canada.

Another reason that the rate of acculturation was

slower here than elsewhere was that Christian missionaries were not as

active in Gaspé as in other parts of New France. There were

Recollets at Percé from about 1675 to 1690. There was also a

secular priest at Pabos, Grand-Rivière for a few years in the

1750s, but he did not seem to be interested in proselytizing Indians.

Nor were the Indians ever drawn into European conflicts in Gaspé

because all military activity in this area was naval.

The Indians of this harsh land were never very

populous. They had a village of perhaps 100 souls at the mouth of the

Restigouche River,4 an area which few French ever had

occasion to visit. In winter the Indians withdrew into the woods to

hunt, but it was hunting for subsistence purposes, not for furs to

trade. So, while Europeans fought and killed one another for this land,

the Micmacs continued to roam the more remote areas of Gaspé,

never feeling threatened enough to attempt resisting the European

intrusion.

The French, however, were continually faced with

intrusive challenges from other Europeans like the English and the

Scots, and even with quarrels among themselves. Nearly every armed

conflict involving the French in America was felt in Gaspé. In

some cases the only effect felt was the arrival of refugees: in 1613 the

English captured Port Royal and sent a group of French in boats to

Gaspé where they found French fishing ships to return them to

France.5 The internecine war in Acadia involving Daulnay,

Denys and LaTour was felt even in Gaspé, for in 1650, one of Mme.

Daulnay's ships was seized there.6 But more important were

the occasions when Gaspé changed hands, whether on paper or

through outright conquest.

In 1621, Sir William Alexander, Earl of Stirling,

convinced James I, King of England and Scotland, of the need to

establish a New Scotland to compare with New England and New France. For

this purpose, Alexander was granted an immense territory including

Acadia and Gaspé. He never succeeded in planting a permanent

colony on his grant, but his claim was temporarily solidified in 1629

when England conquered all of New France.

In 1628, four vessels bound for Quebec with 400

colonists (France's best colonizing effort yet) were forced to land in

the Bay of Gaspé. The commander, Claude de Roquemont, had heard

that the English under David Kirke controlled the St. Lawrence. In

Gaspé, de Roquemont lightened his ships by unloading some of his

cargo. Despite the war with England, France had sent the expedition

without a naval escort, so when de Roquemont eventually left the bay to

try to reach Quebec, all his ships were taken by Kirke. Kirke destroyed

the French cargo stored at Gaspé but took two of the French ships

back to England and there joined with Alexander to finance another

expedition which took Quebec in 1629. By this time peace had been agreed

upon in Europe but New France was not returned until 1632. Emery de Caen

was named commandant of New France and sent to reclaim the colony,

landing in Gaspé Bay on 6 June, and at Quebec a month

later.7

Other wars in Europe, including that between William

III (of Orange) and Louis XIV, seriously affected New France and

Gaspé in particular. In August, 1690, two corsairs, most likely

authorized by the colony of New York, pillaged and destroyed the ships,

fish, missions and villages on îles Percé and Bonaventure.

The residents who had fled into the forests returned but had to flee

again a month later, escaping to Quebec by chaloupe, on the

approach of the expedition being led against Quebec by Sir William

Phips. Phips destroyed the tiny settlement at Petite-Rivière (in

Baie-des-Morues) but failed to take Quebec.8

It was many years before the French again tried to

plant permanent settlements in Gaspé. French fishing vessels

occasionally visited Gaspé during the next 23 years of almost

constant war and many were captured. There was peace in 1697, but only

five years later difficulties in Europe over the succession to the

Spanish throne saw England and France on opposite sides again. In 1711,

an immense expedition led by Sir Hovenden Walker was sent to seize

Quebec in reprisal for Franco-Indian raids. There was little in

Gaspé to attract Walker to stop and destroy en route, but bad

weather forced him to take refuge in the Bay of Gaspé anyhow.

Here he found only one French fishing vessel, which he burned. Soon the

flotilla sailed on to its doom on the rocks of Egg Island in the St.

Lawrence, far distant from Quebec. The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) provided

the French with 30 years of peace to resume development of Canada and

Gaspé, but now they had lost most of Newfoundland and Acadia. The

treaty was unclear as to the limits of Acadia, and while the French

claimed that it ended at Chignecto, some English considered it to extend

to Cap-des-Rosiers. The Council of Nova Scotia reported in 1732 that

Ever Since the french were drove out of Canso ...

They have settled a Great ffishery at Cape Gaspy in his Majestys

Dominions, Where they have Been unmolested for these several years past;

and if they are Not Speedily Drove from thence, they May in time so

ffortify themselves as to Dispute a Great part of his Majestys

Territories in the Bay of St. Lawrence... which if permitted, will

Consequently affect the trade and Navigation of Great

Britain.9

As is particularly evident during the War of the

Austrian Succession (1744-48), the fisheries of Gaspé were envied

by New England and regarded as an important consideration for going to

war again with France.10 Conquest, however, necessitated

destruction of the very sedentary fisheries themselves and, as Father

LeClercq noted, the Indians of Gaspé observed this European

madness for cod with great amusement.11 But unlike Indians in

other European colonies, those of Gaspé were never enticed or

forced into participating in the hunt for cod or in the wars for it.

Although steadily becoming dependent on European manufactured goods

through their occasional fur trade, and although it was their land for

which the Europeans were fighting, the Indians felt no threat to their

land or their lives and were able to remain aloof.

In the 1720s, the French began the great fortress at

Louisbourg to protect the Gulf of St. Lawrence shipping entrance to

Canada and at the same time they came to realize the strategic

importance of Gaspé. Although they did not erect fortifications

at Gaspé during the war of 1744-48 and the Seven Years' War, they

maintained a vigilant lookout there to forewarn Quebec of the approach

of English ships. The inhabitants of Gaspé could never hold out

against a true invasion without soldiers and fortifications and the

settlements there easily fell to Wolfe coming from Louisbourg in 1758.

Wolfe leveled the growing fishing establishments at

Grande-Rivière, Pabos, Gaspé Bay and Mont-Louis, destroyed

36,000 quintals (hundredweight) of fish and transported hundreds of

settlers to France.

This time the English would keep Gaspé: it

would not be returned to the French or left to the Indians. By 1760,

Acadian refugees had gathered at the mouth of the Restigouche. They were

joined by a French flotilla which had come to relieve the siege of

Canada but had arrived too late: it was subsequently destroyed by the

English. This was the last French resistance to English

domination.12 Many Acadians stayed and multiplied on the

south shore but many also moved northward along the coast. Here they

were joined by several families which had lived in Gaspé before

the Conquest. By 1765, there were over 200 Europeans settled on the

south shore and over 100 at Gaspé Bay—already a third of

them were English.13 Within a few years the European

population was swelled by fishermen from Jersey and Guernsey and by

Loyalists from the United States. Gaspé then became unmistakably

European; jurisdictionally British, and socially English and French.

But to whom does Gaspé really belong? The

Royal Proclamation of 8 October 1763 guaranteed the Indians possession

of such land "as not having been ceded to or purchased by Us [i.e., the

Crown]."14 The Indians of Gaspé never ceded or sold

any land to the Crown, nor were they ever conquered. Today they live on

two small reserves on the Bay of Chaleurs.15

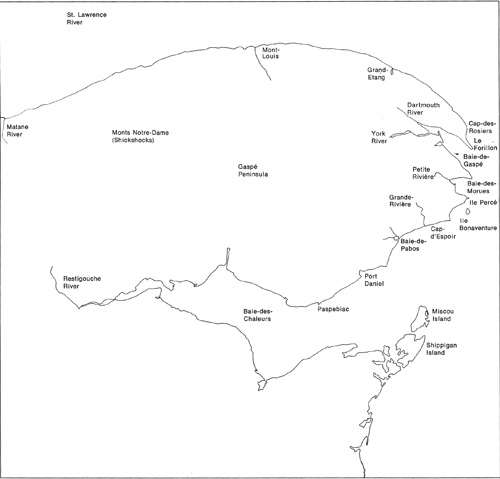

1 Map of the Gaspé peninsula.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

|